A Primer on “Canaries in the Coal Mine? Six Facts About the Recent Employment Effects of Artificial Intelligence”

Breaking down how AI is shaping the labor market

Key takeaways:

22–25-year-olds really are experiencing declining employment in AI-exposed jobs like software development and customer service

While jobs automated by AI are seeing declining entry-level employment, jobs augmented by AI are not

Overall, the job market for experienced workers is holding up, but for entry-level workers it has been stagnant

My colleagues Erik Brynjolfsson, Ruyu Chen and I document these and other facts about AI and jobs in our new Stanford Digital Economy Lab working paper. Here’s an overview of our paper and how we got here.

Lay of the land: what do we know about how AI is impacting jobs?

Since the spread of generative artificial intelligence, there has been uncertainty and fear about how it might affect the labor market. Will our work be replaced by AI, or will we continue to adapt and find new forms of employment?

The discourse spans utopian predictions of enhanced productivity, dystopian fears of widespread job displacement, and skeptical views that AI will just be like any other normal technology.

Recently these questions have been hotly contested: Are we already seeing changes in the labor market driven by AI? How is it impacting young workers?

Some note rising unemployment for college graduates, declines in job postings since 2022, or recent tech layoffs. Others point out that some of these trends preceded AI and that lots of other changes were happening in the economy.

So what’s actually happening? Why don’t we have a definitive answer on how the job market is changing in the sort of work that AI is most capable of doing?

The challenge: getting real-time data on canaries in the coal mine

The problem is that the workhorse data sets researchers use to track the labor market weren’t built to analyze such specific occupations or age groups in real time. There is no publicly available data that can specifically tell us about the condition of software developers between the ages of 22 and 25 in May 2025 with a reasonable amount of confidence, for example.

I know this from experience, having written a paper just a few months ago to track if AI was causing job loss. While I could rule out widespread labor market disruption overall, the data were not detailed enough to reliably track the specific ages and occupations that people are most concerned about, the “canaries in the coal mine” for potential disruption from AI.

We partnered with ADP to solve this problem.

Large-Scale, Real-Time Data on the Labor Market

ADP is the largest payroll software company in the United States, with a market capitalization over $100 billion. Our team at Stanford uses their data to track the state of the economy.

We decided to apply the data towards studying the effect of AI on the labor market. Once we saw the results, we knew we had to share them with the public to inform the current debate.

Entry-level work has declined significantly in jobs exposed to AI

A lot of the recent discussion around AI and jobs has focused specifically on young software developers. Each week more news stories come out chronicling young people’s struggles finding work in the industry.

It turns out these anecdotes in the media are borne out in the ADP data. Employment for 22 to 25 year old software developers in the ADP data is down nearly 20% between its peak in late 2022, around the time of ChatGPT’s launch, to July 2025. Employment for 26 to 30 year olds has also declined slightly, while amazingly for older age groups there is no noticeable change in employment trends.

Surprisingly, we see a similar pattern for customer service representatives, another job often considered exposed to AI.

What about jobs that aren’t so exposed to AI? A good example is nursing, psychiatric, and home health aides, whose work requires them to be in person and often perform physical tasks for patients. We actually see the opposite pattern for health aides as we saw for software and customer service, with the youngest age group having the fastest growth in employment.

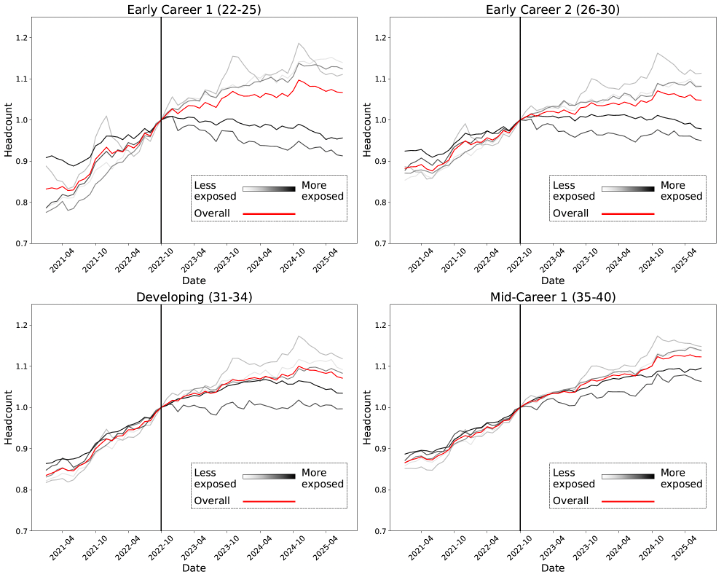

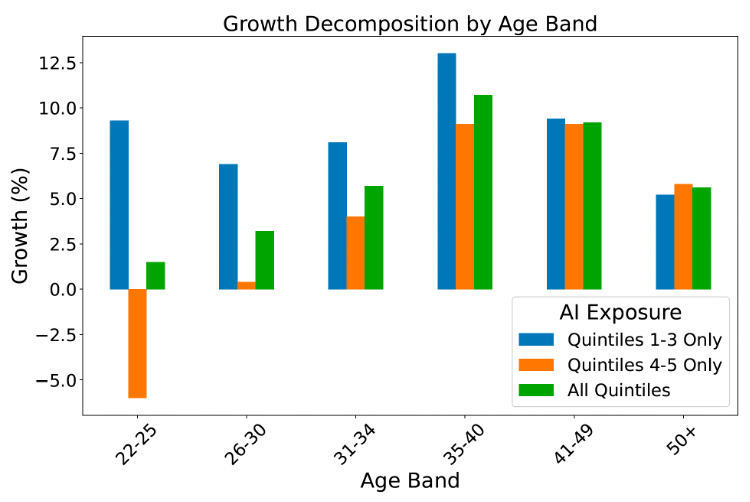

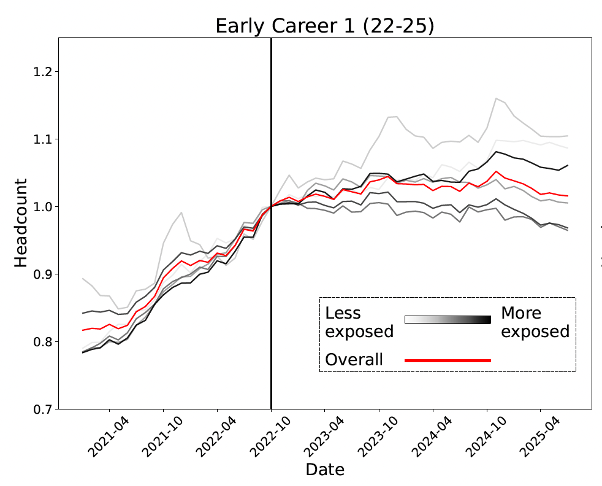

We found that these broad trends are not limited to just these case studies. For 22- to 25-year-olds, employment is rising in the least AI-exposed jobs like for health aides but notably declining in the most exposed jobs like software development or customer service. In contrast, for older age groups we see no meaningful divergence in employment patterns by AI exposure.

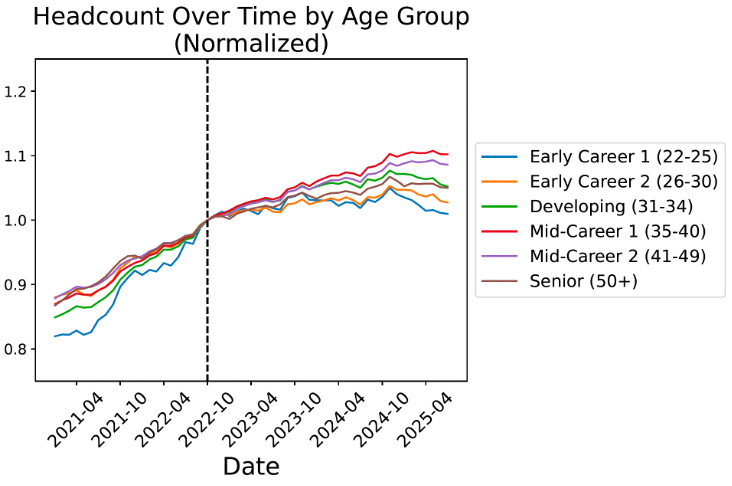

Employment growth for young workers is stagnating even as growth for older workers remains robust

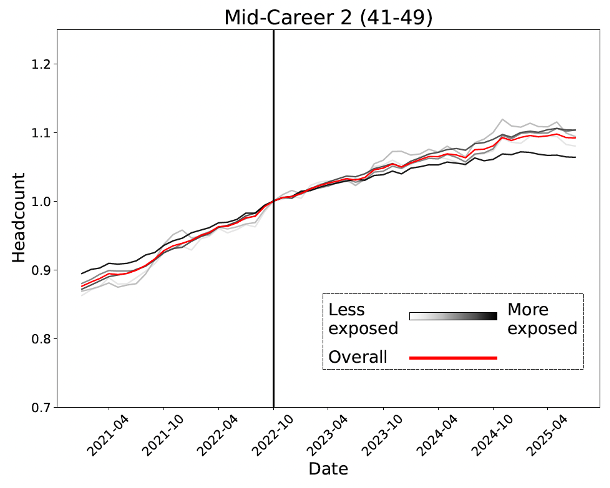

This slowdown in hiring for AI-exposed jobs is driving overall stagnation in the labor market for young workers. While older workers continue to see employment growth, employment for young workers in the ADP data has been nearly flat since late 2022.

This pattern for young workers is surprisingly driven by reduced employment in the most AI-exposed jobs, with growth in less-exposed jobs similar across age groups.

Of course, these results deserve a word of caution. We do not claim that these findings are fully driven by AI. Many other things changed in the US economy at the same time. The trend for software developers in particular is probably not fully explained by AI given how quickly the employment decline occurs after late 2022.

The next step is to test how the results hold up when considering alternative ways of analyzing the ADP data.

Entry-level employment has declined in applications of AI that most automate work, but not ones that most augment it

Not all applications of AI need to automate work. Some uses may augment what we do. A good example is using AI to learn and develop new skills that make us more productive.

We next studied if employment changes are similar in jobs where AI augments work instead of automates it.

We used data from the Anthropic Economic Index, which includes estimates of whether Claude conversations related to an occupation are more automative or augmentative. Jobs with high levels of automative usage include things like computer programming and accounting, while occupations like management or repairs have a high share of augmentative usage.

While we see a decline in employment for young workers in jobs with high automative LLM usage, we do not see the same pattern in jobs with high augmentative usage. The jobs with the most augmentative usage have actually seen robust employment growth.

These results are consistent with the idea that automative uses of AI substitute for human labor while augmentative uses do not.

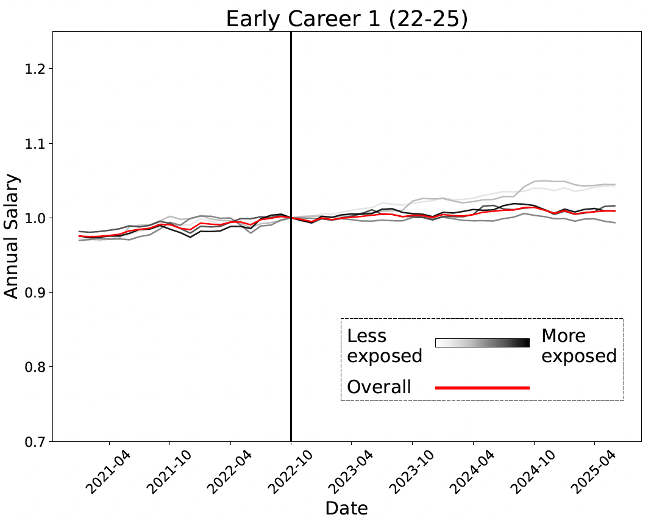

We do not see meaningful changes in workers’ salaries

Given the large employment effects, we might also expect changes in how much workers get paid. We used the annual salary data in ADP to track how pay is changing by age and AI exposure.

It turns out we do not see meaningful differences in pay growth by age or occupation.

Why don’t we see bigger impacts on compensation? This is an interesting question worth investing further research in.

One possibility is that employment adjust more quickly than wages. Another is that AI changes the expertise requirements across different roles in ways that lead to muted overall impacts on earnings. We don’t yet have a definitive answer.

Okay, but what about alternative explanations?

Of course, you might be skeptical that these changes are driven solely by AI. We wanted test out other theories ourselves, so we considered various other ways of cutting and analyzing the data.

First, what if these trends are just driven by the tech sector? Tech companies may have overhired during the pandemic and subsequently cut back on their workforce. It turns out that our results are very similar when we exclude the tech sector or people in computer-related jobs.

Could it be explained by return-to-office requirements after the work-from-home boom during COVID? We get very similar results for occupations that are not amenable to work from home, such as bank tellers, tax preparers, and travel agents.

The pandemic also harmed education outcomes for students. Perhaps we observe these trends because entry-level workers are less prepared to enter the workforce in recent years.

In fact, we found very similar results in occupations where most people do not have a college degree. For less-educated occupations, we actually see employment effects at even higher age ranges, up to age 40. These results make it unlikely that changes in education fully explain our findings.

While more educated people work in jobs that have higher average AI exposure overall, these findings suggest that less educated workers get less protection from AI with greater experience. More on this shortly.

Finally, in the paper we do a formal statistical test for whether our results are driven by broader shocks to the US economy that have different effects across distinct firms or industries. We again find the big, statistically significant effects for young workers in the most exposed jobs even after accounting for these factors, in line with our main figures and findings.

Overall, we do not want to claim that AI explains all of the patterns we show in the data, but our results are consistent with the notion that AI is having a tangible impact on the labor market for entry-level workers.

Why entry-level workers?

One of the most surprising things about our results is that the effect is so acute for entry-level workers. Why might AI have a disproportionate effect on people just entering the workforce?

There still needs to be more research to understand this better. One possibility is that, given the nature of the AI model training process, AI is exceptionally good at the sort of knowledge that can be learned from books or that make up the core of formal education. AI may be less capable at learning the sort of tacit knowledge that comes from experience on the job. This may also line up with what we see for less educated occupations since the benefits to experience might be lower on average in those jobs.

This is not the only story that could explain what’s going on. Another possibility is that companies are in a holding pattern as they experiment with whether AI can improve productivity or save on labor costs. It might be easier for them to avoid hiring new workers than to let go of existing workers during this adjustment process, which could explain why we see disproportionate employment impacts for entry-level workers but limited salary impacts overall. Under this theory the employment impacts would still ultimately be caused by AI but under a very different channel. As firms learn more about how to integrate AI into their processes they may even reverse course and hire back more young people.

The true answer might be something in between or something else entirely. My coauthors and I will continue tracking these trends so that we can reach a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms.

As a final note, are our results truly so dour for how AI is impacting the labor market?

Impactful new technologies always lead to adjustment periods with some workers benefiting more than others. Over time workers shift from displaced forms of work to ones with growing demand. We may already be seeing such shifts, with some evidence of declining numbers of computer science majors. Technological change tends to result in growing employment and real wages overall, with the gains not accruing to everyone equally. Tracking these trends on an ongoing basis will help us assess if AI is following a similar pattern. Hopefully it will also give guidance on how to best support those who may be harmed in the labor market.

Very interesting findings, and consistent with the anecdotal evidence from the news media...

Damn it, I don't wanna have to switch from CS to nursing.